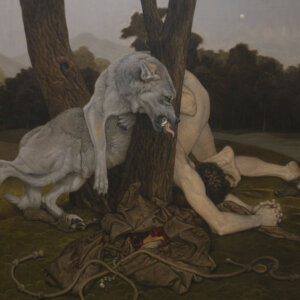

Durante a década de 1920, Sutherland produziu uma série de gravuras e desenhos diretamente inspirados no exemplo de Samuel Palmer. A série culminou neste trabalho, cujas formas simplificadas e técnicas detalhadas lembram Palmer. No entanto, as sombras estranhas e os troncos de árvores bizarramente retorcidos atingem uma nota mais pessoal. Aqui Sutherland transforma a evocação de um idílio arcadiano em uma imagem mais pagã, substituindo o simbolismo cristão tradicional por forças animistas. O senso de drama meditativo visto aqui foi desenvolvido nas pinturas de paisagens de Sutherland no final da década de 1930 e início da década de 1940.

Pastoral 1930 Graham Sutherland OM 1903-1980 Purchased 1970 http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/P07117

Na série The Crown, nono episódio (dos dez da 1ª temporada) chamado Assassins, testemunhamos a troca inicial entre o artista reservado e o impetuoso primeiro-ministro britânico. Ambas as figuras são reservadas e habilmente se avaliam. À medida que as sessões continuavam e o dia da apresentação da tela se aproximava, Churchill ficou mais apreensivo. Ele começou a pesquisar o estilo de Sutherland e o questionou, de brincadeira e depois, de maneira direta. Da mesma forma, Sutherland analisou algumas das pinturas de Churchill e respondeu em espécie. O diálogo resultante foi um pináculo de pungência que capturou a beleza ideal da arte alimentada pela profunda dor da realidade.

Churchill: Do you think I’ll like it?

Sutherland: I think that’s possibly too much to ask for. But I do take comfort from the fact that your own work is so honest and revealing.

Churchill: Oh, thank you for the compliment. Well, are there any works that you’re referring to in particular?

Sutherland: I was thinking especially of the goldfish pond here at Chartwell.

Churchill: The pond? Why the pond? It’s just a pond.

Sutherland: It’s very much more than that. As borne out by the fact that you’ve returned to it again and again. More than twenty times.

Churchill: Well, yes, because it’s such a technical challenge. It eludes me.

Sutherland: Well perhaps you elude yourself, sir. That’s why it’s more revealing than a self-portrait.

Churchill: Oh, that’s nonsense. It’s the water, the play of light. The trickery. The fish, down below.

Sutherland: I think all our work is unintentionally revealing and I find it especially so with your pond. Beneath the tranquility and the elegance and the light playing on the surface, I saw honesty and pain, terrible pain. The framing itself, indicated to me that you wanted us to see something beneath all the muted colors, deep down in the water. Terrible despair. Hiding like a Leviathan. Like a sea monster.

Winston Churchill, The Goldfish Pool at Chartwell (1932).

Churchill: You saw all that?

Sutherland: Yes, I did.

Churchill: Perhaps that says more about you than me?

Sutherland: Perhaps.

Churchill: May I ask you a question, Mr. Sutherland? It’s about one of your paintings. It’s about the one you call “Pastoral”. With all that gnarled and twisted wood. Those great ugly dabs of black. I found something malevolent in it. Where did that come from?

Sutherland: Well, that’s very perceptive. That was a very dark time. My… my son, John, passed away, aged two months.

Churchill: Oh my. I am sorry.

Sutherland: Yes. Thank you. You have five, yes?

Churchill: Four. Marigold was the fifth. She left us at age two years, nine months. Septicemia.

Sutherland: I’m so sorry. I had no idea.

Churchill: We settled on the name Marigold, on account of her wonderful golden curls. The most extraordinary color. Regretfully, but though perhaps mercifully, I was not present when she died. When I came home, Clemmie roared like a wounded animal. We bought Chartwell a year after Marigold died. That was when… I put in the pond.

Por um momento, em luto, o artista e o primeiro ministro se entenderam. Por um momento, eles eram irmãos improváveis. Sua arte serviu como uma saída que obscureceu e revelou as profundezas de seu desespero. As pinceladas pintaram imagens da beleza ideal, mas de verdade muito real.

Quando a pintura de Graham Sutherland foi revelada perante o Parlamento, Winston Churchill ficou mortificado. Ali, ele viu decadência e desmoralização. Em particular, ele chamou o retrato de maligno e o cortou e queimou. Sutherland, no entanto, viu o leão da Grã-Bretanha não menos heróico, apenas temperado pela agridoce idade. Os dois homens seguiram seus caminhos. E ambos voltaram a pintar novamente.

Sutherland (1903–1980)