Expressão máxima do erotismo universal e texto de estreia de Georges Bataille, História do olho é também sua obra mais célebre e um dos maiores clássicos da literatura do século XX.

Chocante e sacrílega, esta novela é a expressão da obsessão do autor pela proximidade entre sexo, violência e morte, e sua dimensão filosófica se depreende do exercício ilimitado que Bataille faz de tal relação.

Publicado em 1928 sob o pseudônimo de Lord Auch, o livro acompanha as peripécias sexuais do jovem narrador e de sua amiga Simone. Embebido da atmosfera do surrealismo francês, do qual o próprio Bataille chegou a fazer parte, o relato suspende do horizonte das personagens o interdito do universo adulto e propicia aos jovens uma jornada de extravagâncias que envolvem sadismo, orgias, tortura e loucura, culminando em um ato de transgressão.

“Para os outros, o universo parece honesto. Parece honesto para as pessoas de bem porque elas têm os olhos castrados. É por isso que temem a obscenidade. […] apreciam os ´prazeres da carne´, na condição de que sejam insossos.”

textos do Apêndice: Michel Leiris faz uma análise biográfica da História do Olho, enquanto Roland Barthes faz uma análise linguística e Julio Cortázar fecha com uma poética crônica sobre os selins de bicicleta.

“a diversão é a necessidade mais gritante e, é claro, mais terrificante da natureza humana”

“Era durante a qual os tabus imemoriais são violados sistematicamente por esses jovens deuses ansiosos e turbulentos, o narrador e Simone, e por seu acólito, os três tentando infinitamente ocupar seu ócio absoluto com os gestos aberrantes que exige sua sede inextinguível de se sentir ao mesmo tempo fora de toda lei e fora de si mesmos (…)”

Enquanto isso, o céu ameaçava uma tempestade e, com a noite grossos pingos de chuva haviam começado a cair, aliviando a tensão de um dia tórrido e sem ar. O mar fazia um barulho enorme, dominado pelos fortes estrondos dos trovões, e os relâmpagos permitiam ver, como à luz do dia, os dois cus excitados das meninas então emudecidas. Um frenesi brutal agitava nossos três corpos. Duas bocas juvenis disputavam meu cu, meus colhões e meu pau, e eu não parava de abrir pernas úmidas de saliva e porra. Era como se eu quisesse escapar do abraço de um monstro, e esse monstro era a violência dos meus movimentos. (…) A violência dos trovões nos assustava e aumentava nossa fúria, arrancando-nos gritos que ficavam mais fortes a cada relâmpago, ante a visão de nossos séculos.

Para os outros o universo parece honesto. Parece honesto para as pessoas de bem porque elas têm os olhos castrados. É por isso que temem a obscenidade. Não sentem nenhuma angústia ao ouvir o grito do galo ou ao descobrirem o céu estrelado. Em geral, apreciam os “prazeres da carne”, na condição de que sejam insossos.

Kiril Bikov is Bulgarian, but living and working in Berlin. His photography reflects a critical engagement with his interests in thanatology (the study of death)

eu não gostava daquilo a que se chama “prazeres da carne”, justamente por serem insossos. Gostava de tudo o que era tido por “sujo”. Não ficava satisfeito, muito pelo contrário, com a devassidão habitual, porque ela só contamina a devassidão e, afinal de contas, deixa intacta uma essência elevada e perfeitamente pura. A devassidão que eu conheço não suja apenas meu corpo e os meus pensamentos, mas tudo o que imagino em sua presença, e sobretudo, o universo estrelado…

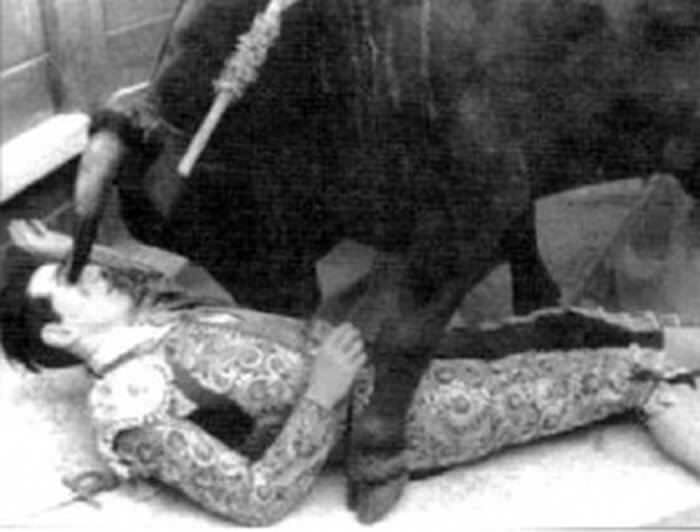

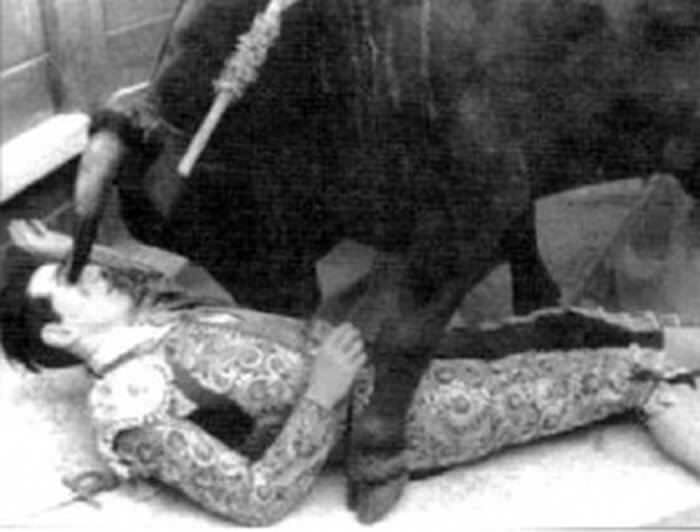

Flying Bull during a Bullfight Spain by Felipe Rodriguez

Toda representação do tédio está associada, para mim, a este momento e ao cômico obstáculo que é a morte.

Essa alucinação pessoal se desenrolava agora com a mesma falta de limites que o pesadelo global da sociedade humana, por exemplo, com a terra, a atmosfera, o céu.

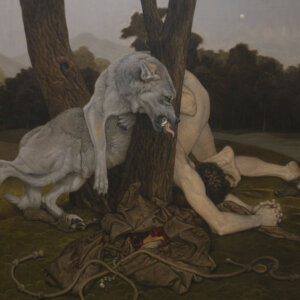

Cover illustration from Ögate Historia by Georges Bataille

On May 7, 1922, the toreadors La Rosa, Lalanda and Granero were to fight in the same arena of Madrid: the last two were renowned as the best matadors in Spain, and Granero was generally considered superior to Lalanda. He had only just turned twenty, yet he was already extremely popular, being handsome, tall and still of a childlike simplicity. Simone had been deeply interested in his story, and exceptionally, had shown a genuine pleasure when Sir Edmund announced that the celebrated bull-killer had agreed to dine with us the evening of the fight.

A Bullfight in Lima by Gustaf Tenggren (1919)

Granero stood out from the rest of the matadors because there was nothing of the butcher about him: he looked more like a very manly Prince Charming with a perfectly elegant figure. In this respect, the matador’s costume is quite expressive, for its safeguards the straight line shooting up so rigid and erect every time the lunging bull grazes the body and because the pants so tightly sheathe the behind. a bright red cloth and a brilliant sword (before the dying bull whose hide steams with sweat and blood) completes the metamorphosis, bringing out the most captivating features of the game. One must also bear in mind the typical torrid Spanish sky, which never has the colour or harshness one imagines: it is just perfectly sunny with a dazzling but mellow sheen, hot, turbid, at times even unreal when the combined intensities of light and heat suggest the freedom of the senses.

Spanish bullfighter Cayetano Rivera performs at the Plaza Valencia, Spain

Now this extreme unreality of the solar blaze was so closely attached to everything that was happening around me during the bullfight on May 7, that the only objects I have ever carefully preserved are a round paper fan, half yellow, half blue, that Simone had that day, and a small illustrated brochure with a description of all the circumstances, and a few photographs. Later on, during an embarkment, the small valise containing these two souvenirs tumbled into the sea, and was fished out by an Arab with a long pole, which is why the objects are in such a bad state. But I need them to fix that event to the earthly soil, to a geographic point and a precise date, an event that in my imagination compulsively pictures as a simple vision of solar deliquescence.

Juan Jose Padilla by AP

The first bull, the one who’s balls Simone looked forward to serving raw on a plate, was a kind of black monster, who shot out of the pen so quickly that despite all efforts and all shouts, he disembowelled three horses in a row before an orderly fight could take place; one horse and rider were hurled aloft together, loudly crashing down behind the horns. But when Granero faced the bull, the combat was launched with brio, proceeding amid a frenzy of cheers. The young man sent the furious beast chasing around him in his pink cape; each time, his body was lifted by a sort of spiraling jet, and he just barely eluded a frightful impact. In the end, the death of the solar monster was performed cleanly, with the beast blinded by the scrap of red cloth, the sword deep in the blood-smeared body. An incredible ovation resounded as the bull staggered to its knees with the uncertainty of a drunkard, collapsed with its legs sticking up, and died.

Simone, who had sat between Sir Edmund and myself, witnessed the killing with an exhilaration at least equal to mine, and she refused to sit down again when the interminable acclamation for the young man was over.

Illustration from More English Fairytales collected and edited by Joseph Jacobs and illustrated by John D Batten, published by D Nutt (London, 1894)