“On Visiting the Grave of my Stillborn Little Girl”

I made a vow within my soul, O child,

When thou wert laid beside my weary heart,

With marks of Death on every, tender part,

That, if in time a living infant smiled,

Winning my ear with gentle sounds of love

In sunshine of such joy, I still would save

A green rest for thy memory, O Dove!

And oft times visit thy small, nameless grave.

Thee have I not forgot, my firstborn, thou

Whose eyes ne’er opened to my wistful gaze,

Whose suff’rings stamped with pain thy little brow;

I think of thee in these far happier days,

And thou, my child, from thy bright heaven see

How well I keep my faithful vow to thee.

Elizabeth Gaskell

(Sunday, July 4th, 1836)

“Ao visitar o túmulo de minha menina natimorta”

Fiz um voto em minha alma, ó criança,

Quando você foi posta ao lado do meu coração cansado,

Com marcas da morte em todas as partes tenras,

Que, se com o tempo uma criança viva sorrisse,

Ganhando meus ouvidos com sons suaves de amor

No sol de tanta alegria, eu ainda salvaria

Um verde descanso para tua memória, ó Pombinha!

E por vezes visito seu túmulo pequeno e sem nome.

Não te esqueci, minha filha primeira, tu

Cujos olhos nunca se abriram ao meu olhar melancólico,

Cujos sufrágios marcados com dor em tua testa;

Penso em ti nestes dias muito mais felizes,

E tu, minha filha, do teu céu brilhante vê

Quão bem mantenho meu voto fiel a ti.

Elizabeth Gaskell

(Domingo, 4 de julho de 1836)

Tradução de Julia Medrado

A maior parte do trabalho existente de Gaskell antes de Mary Barton consiste em uma escrita que demonstra sua intensa interioridade, e seu diário, em particular, manifesta o papel que a escrita desempenhou na sua intimidade e autorregulação. Embora já estivesse empenhada em escrever para o público, Gaskell também escreveu ativamente em seu diário como meio de falar e exercer a maternidade. Enlutada, Gaskell escreveu não apenas após a morte de Willie, seu bebê de poucos meses, mas também em 1836, com um soneto relembrando sua primeira filha, natimorta em 1833. Ela usou as páginas do diário para avaliar e determinar as melhores práticas maternas para criar suas quatro filhas que vieram depois. Escreveu com angústia e medo por causa das doenças e riscos frequentes. E, acima de tudo, ela escreveu para preservar seu relacionamento materno além das mortes que temia e esperava. Escrever, para Gaskell, era um meio de moldar sua própria identidade como mãe e um meio de ser mãe não apenas de suas filhas, mas de si mesma, órfã de mãe muito cedo.

Ao longo do diário, Gaskell emprega seu estilo para descrever vividamente e representar seus medos de perda. Na segunda entrada, Gaskell escreve sobre uma doença passada de Marianne, na qual ela temia pela vida de sua filha: “Não posso dizer como fiquei doente em meu coração, só de pensar em não vê-la mais aqui.

“Her empty crib to see

Her silent nursery,

Once gladsome with her mirth.”

(Journal, August 4, 1835)

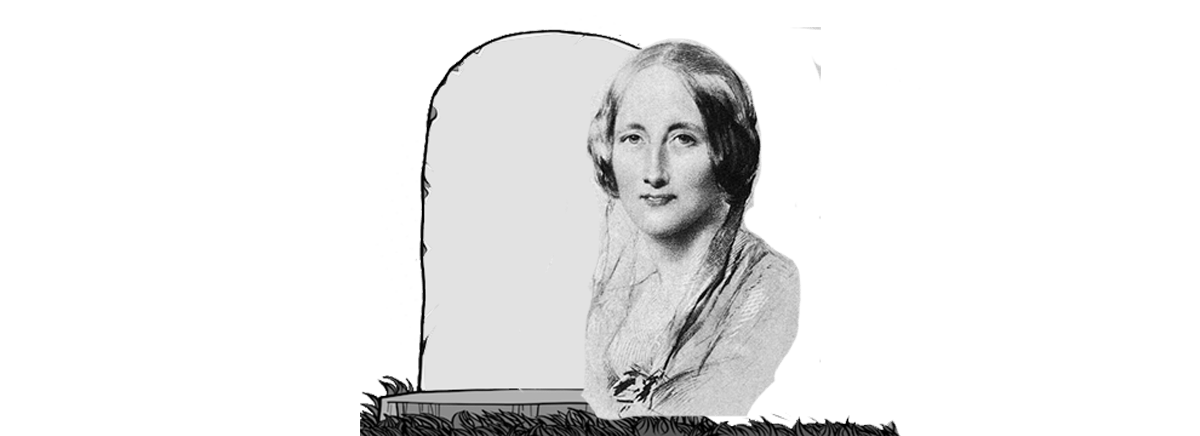

Elizabeth Cleghorn Gaskell 🇬🇧 (1810-1865), muitas vezes chamada simplesmente de Mrs Gaskell, foi uma romancista e contista britânica da era vitoriana. Seus romances oferecem um retrato detalhado das vidas de muitos estratos da sociedade, incluindo os muito pobres, e como tal são de interesse para os historiadores sociais, bem como para os amantes de literatura. Seu primeiro romance, Mary Barton, foi publicado em 1848. A The Life of Charlotte Brontë, de Gaskell, publicada em 1857, foi a primeira biografia de Brontë. Alguns dos romances mais conhecidos de Gaskell são: Cranford (1853), North and South (1855) e Wives and Daughters (1865).

Elizabeth Cleghorn Gaskell 🇬🇧 (1810-1865), muitas vezes chamada simplesmente de Mrs Gaskell, foi uma romancista e contista britânica da era vitoriana. Seus romances oferecem um retrato detalhado das vidas de muitos estratos da sociedade, incluindo os muito pobres, e como tal são de interesse para os historiadores sociais, bem como para os amantes de literatura. Seu primeiro romance, Mary Barton, foi publicado em 1848. A The Life of Charlotte Brontë, de Gaskell, publicada em 1857, foi a primeira biografia de Brontë. Alguns dos romances mais conhecidos de Gaskell são: Cranford (1853), North and South (1855) e Wives and Daughters (1865).

Tradução

Julia Medrado (1985–), paulistana, mãe da Patrícia e do Tarcísio, vive em Coimbra – Portugal, é tradutora, publicista e mestre em Literatura e Crítica Literária. Graduada em Letras pela PUC-SP, é também especialista em Gestão de Projetos Digitais pelo SENAC. Presta serviços junto a redatores, revisores e tradutores; em 2010 criou a Tradstar e, desde então, se divide entre projetos, alguns literários e absolutamente pessoais, como este site que leva seu nome.

Julia Medrado (1985–), paulistana, mãe da Patrícia e do Tarcísio, vive em Coimbra – Portugal, é tradutora, publicista e mestre em Literatura e Crítica Literária. Graduada em Letras pela PUC-SP, é também especialista em Gestão de Projetos Digitais pelo SENAC. Presta serviços junto a redatores, revisores e tradutores; em 2010 criou a Tradstar e, desde então, se divide entre projetos, alguns literários e absolutamente pessoais, como este site que leva seu nome.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806-1861) foi uma poetisa inglesa da época vitoriana nascida em Kelloe, Durhan. Autora de Sonnets from the Portuguese, reunião de poemas românticos — sua própria história de amor com o marido, o também poeta Robert Browning. Elizabeth foi a dona do cocker spaniel que inspirou Woolf a escrever Flush.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806-1861) foi uma poetisa inglesa da época vitoriana nascida em Kelloe, Durhan. Autora de Sonnets from the Portuguese, reunião de poemas românticos — sua própria história de amor com o marido, o também poeta Robert Browning. Elizabeth foi a dona do cocker spaniel que inspirou Woolf a escrever Flush.

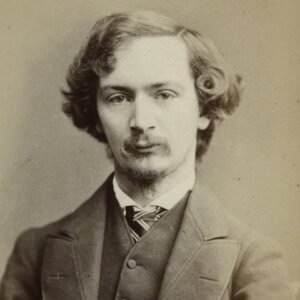

(1837-1909) foi um poeta, dramaturgo, romancista e crítico inglês nascido em Londres, no Reino Unido da época vitoriana, conhecido pela controvérsia gerada no seu tempo pelos seus temas sadomasoquistas, lésbicos, fúnebres e anti-religiosos. Algernon foi indicado para o Prêmio Nobel de Literatura por vários anos do início do século XX.

(1837-1909) foi um poeta, dramaturgo, romancista e crítico inglês nascido em Londres, no Reino Unido da época vitoriana, conhecido pela controvérsia gerada no seu tempo pelos seus temas sadomasoquistas, lésbicos, fúnebres e anti-religiosos. Algernon foi indicado para o Prêmio Nobel de Literatura por vários anos do início do século XX.